Plastic recycling as it exists today, is a scam

Plastic recycling as it exists today, is a scam.

According to a Greenpeace report published in 2022, they found only about 5% of plastic household waste in the U.S. was actually recycled.

That’s down from the EPA estimate of 8.7% in 2018.

While many of us go through the motions of separating out our plastics, the effort is nearly useless.

According to the New Plastics Economy report by the World Bank and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, we discard 95% of plastic packaging material ($80 billion to $120 billion annually) after one use.

Nearly all of the plastic that is recycled once, is discarded afterward.

To summarize that, we throw out up to $120 billion in plastic packaging after one use. And we discard the other $6 billion after two uses. That appears to be a huge opportunity for an innovative company. The problem is an engineering issue. Plastics are simple molecules. We have decades of science on making them.

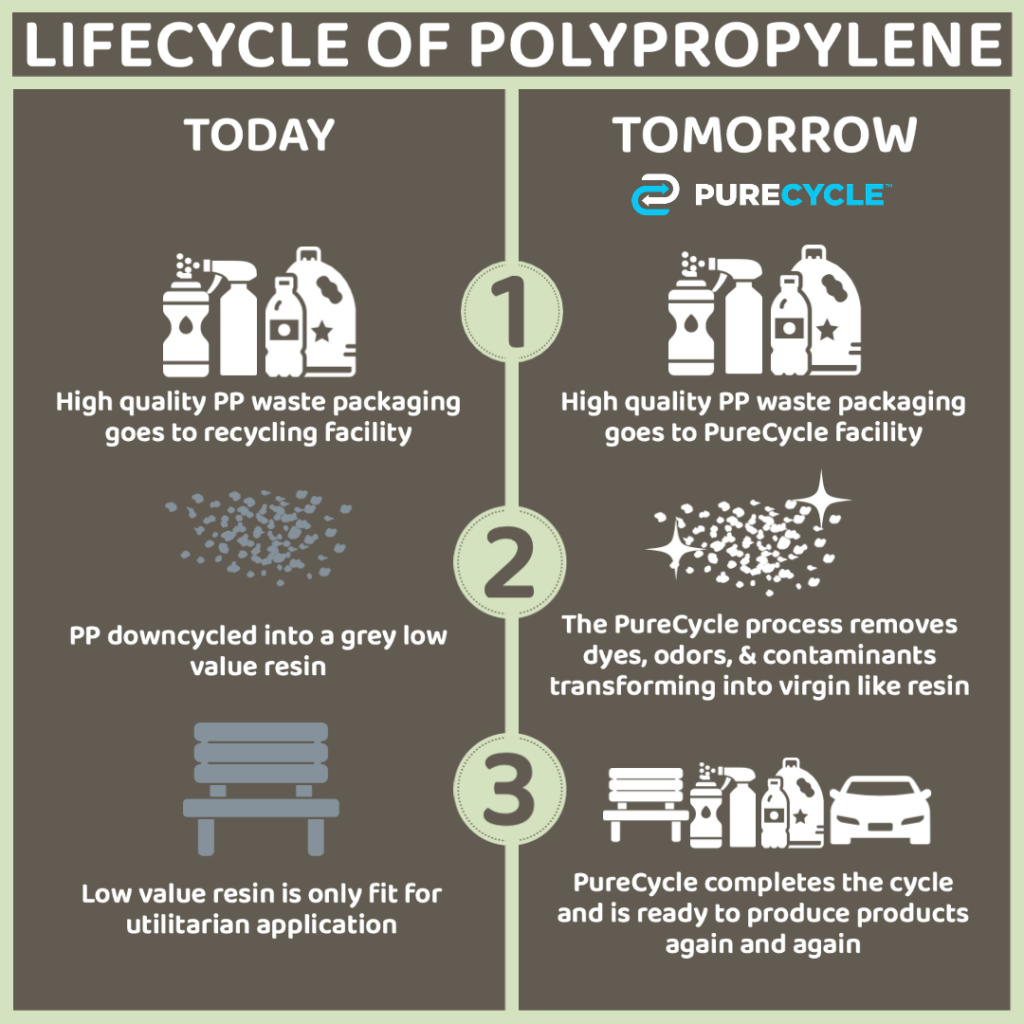

Where we are now:

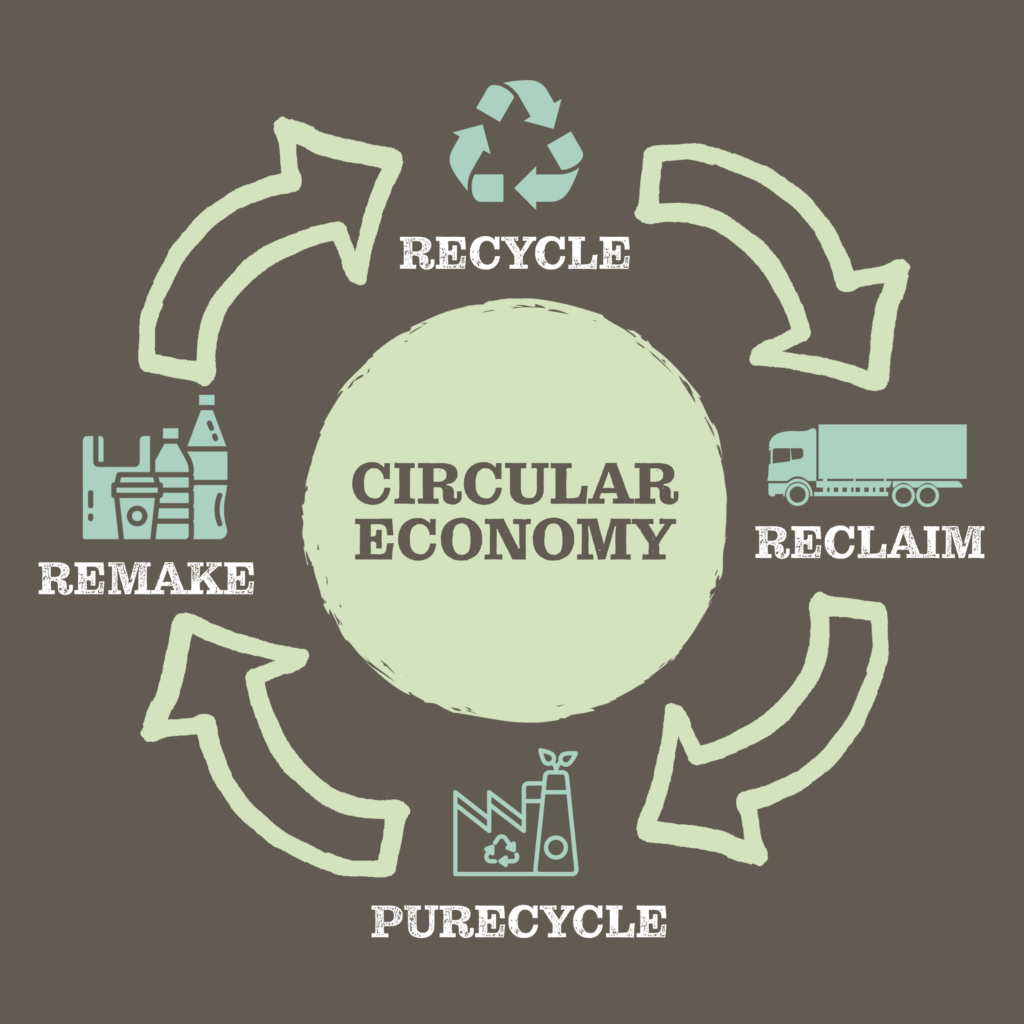

Where we need to be:

We should be able to refine and reuse plastic. It should be economically viable.

There should be an opportunity for some bright chemical engineer to figure it out.

But that opportunity existed for the last 50 years. And the companies that tried failed. The prevailing argument is that recycling isn’t economic. It’s too hard to remove contaminants. Too energy intensive.

This month, we are going to dive into a company that proves recycling plastic can be economic. They are building a full-scale recycling plant that should begin production this month. And they are developing another facility at the Port of Antwerp in Belgium. And they have agreements in place to develop more facilities in South Korea and Japan.

It appears that this company broke the code. And if so, we need to invest in them.

Why is Plastic Recycling so Difficult?

Developed in the 1930’s, plastics began life as a top-secret project during the war. But in the post-war 1950’s, it became the “wonder material”. Polyester clothes became the height of fashion.

But by the 1970’s, plastic trash was everywhere. We began to run out of space in the landfills. The U.S. began to push for recycling. But it was derailed, as you’ll see.

By the early 2000’s, we produced more than 35 million tons of plastic.

We recycled just 3.1 million tons.

On September 11, 2020, National Public Radio’s Planet Money ran a fantastic story called Wasteland, about plastic recycling.

The story centers on the emergence of the recycling symbol in the 1980’s. It’s a little triangle made of arrows, with a number inside it. And it came about because of the 1970’s environmental movement.

You see, the plastics industry knew that recycling plastic was difficult, even back then:

A report was sent to top oil and plastic executives in 1973. It says recycling plastic is nearly impossible. There is no recovery from obsolete products, it says. Recycling is costly. Sorting it is infeasible. Plus, it says plastic degrades every time you try to reuse it. So the oil and plastic industry knew. They’ve known for almost 50 years.

And as the environmental movement grew, so did concerns for plastic sales. Here’s another quote from the Planet Money story:

In one of the documents I found from 1989, Larry wrote to top oil executives at Exxon, Chevron, Amoco, Dow, DuPont, Procter & Gamble and a bunch of others. He wrote, the image of plastics is deteriorating at an alarming rate. We are approaching a point of no return.

They wanted to keep making plastic. But the more you make, the more plastic trash you get. And the obvious solution to this is to recycle it. But they knew they couldn’t. Remember, it’s expensive. It degrades.

That’s when the recycling symbol was born.

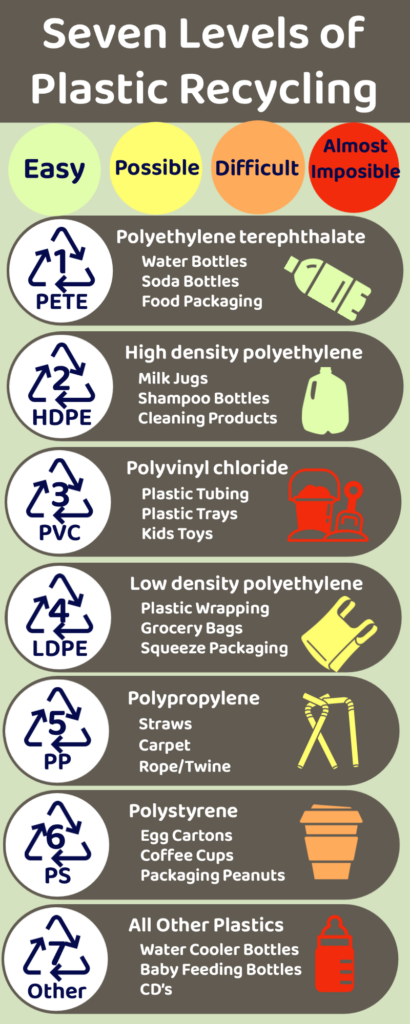

There are actually seven kinds of plastic in use today.

And as you can see, some are easily recyclable while others are impossible.

To make recycling easier, plastic products have more recently been categorized number 1 to number 7.

The assigned code reflects the type of polymer used to make the plastic product.

Each of the resins have unique characteristics and uses.

Among the seven, polypropylene (No. 5 or PP), is one of the most versatile and can be found in cars, food packaging and even furniture.

The industry campaigned in 40 states to require that every single plastic item have the symbol stamped on it. They put it on every plastic piece, even the stuff that couldn’t be recycled. And the industry knew it couldn’t work.

But it wasn’t about the science of recycling. It was about marketing.

The plastic makers (DuPont, Chevron, Amoco, Dow, Proctor & Gamble, etc.) began running ads about recycling plastics.

These commercials carried an environmentalist message, but they were paid for by the oil and plastic companies, eventually leading to a $50-million-a-year industry-wide ad campaign promoting plastic. So I asked Larry, why? Why spend tens of millions of dollars telling people to recycle plastic when they knew recycling plastic wasn’t going to work? And that’s when he said it, the point of the whole thing.

The point was to make you and I believe that they could recycle plastic.

The industry funded all sorts of recycling projects. They created expensive sorting machines. They funded recycling projects in neighborhoods and national parks. They even funded a plan to recycle all the plastic in school lunches in New York.

They all failed and disappeared. But they achieved the goal – we all believed that plastic could be recycled.

So, we kept buying plastic instead of metal or glass.

Today, there is considerable pressure on the industry to change. In The New Plastics Economy report, is the “overarching vision…that plastics never become waste”. Instead, they should be designed to either degrade or be recyclable.

Given plastic packaging’s many benefits, both the likelihood and desirability of an across-the board drastic reduction in the volume of plastic packaging used is clearly low. Nevertheless, reduction should be pursued where possible and beneficial, by dematerializing, moving away from single-use as the default, and substitution by other materials.

If only they industry had spent their marketing budgets on these goals 50+ years ago…but I digress.

The key takeaway here is moving away from single use applications. The report lays out the following points for the future:

- Radically increase the economics, quality, and uptake of recycling

- Scale up adoption of reusable packaging

- Scale up adoption of industrially compostable plastic packaging for targeted applications

The problem we face is that organic contents (food and oils) contaminate the plastic. So, we need two kinds of plastic: degradable and recyclable. These are two different problems. And in this month’s issue, we are dealing with the latter.

In 2021, the world produced over 180 billion pounds of polypropylene, but only recycled 6%. The rest is an opportunity.

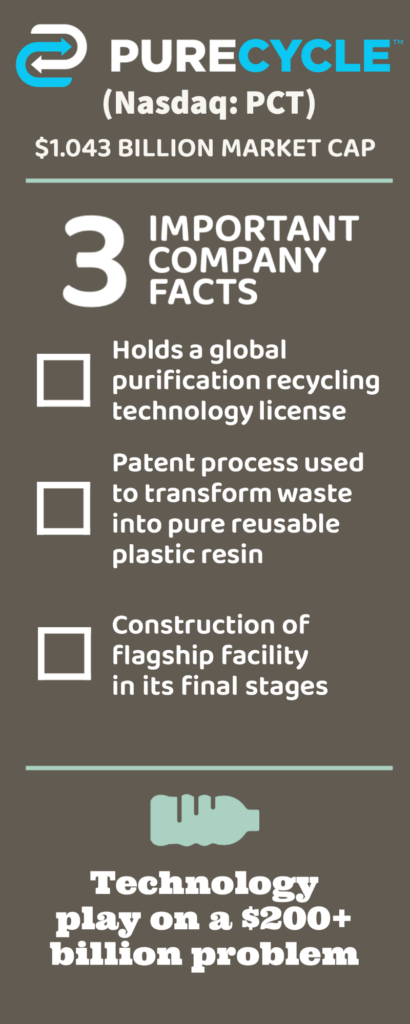

This month’s research target is PureCycle Technologies (Nasdaq: PCT), a polypropylene plastic recycler with a big future.

Closing the Loop on Plastic Recycling 50+ Years Later

PureCycle Technologies (Nasdaq: PCT) is a $1.0 billion plastic recycler. It holds a global license to commercialize the only patented solvent-based purification recycling technology in the world. Proctor & Gamble developed the technology for recycling waste plastic into ultra-pure resin.

The company’s flagship plant is in Ironton Ohio. It will begin producing commercially in April 2023. The company also plans to build a “cluster facility” in Augusta Georgia that will house up to 8 purification lines.

PureCycle are developing another facility at the Port of Antwerp in Belgium. And they have agreements in place to develop more facilities in South Korea and Japan.

The company’s goal is to become the largest player in recyclable polypropylene plastics. They want to move plastic from a limited use material to an endless use material.

The Secret to the Process is Extraction and Filtration

The company uses a patented technology to remove contaminants, colors, and odors from polypropylene plastic waste. They transform waste into an ultra-pure reusable plastic resin.

PureCycle’s process begins with used plastics from consumer packaging, carpet fiber, plastic film, and other trash. The polypropylene gets melted into polymer and large contaminants get filtered out.

The filtered polymer is then dissolved in a solvent. The solvent pulls out the color and odor, like water pulling tea from tea bags. The solvent also separates contaminants and other plastics to settle out. The separated material forms a byproduct stream.

PureCycle then uses filters to continue to purify the polymer. They compare it to using a coffee filter to make sure the grains don’t go into the pot.

Once the polymer is pure, they separate the solvent back out. The solvent is reused, and the polypropylene settles out as a solid.

The benefit of this process is that it doesn’t degrade the plastic.

According to the company, the polypropylene can be used and recycled multiple times.

The resulting resin is easily colorable, 100% recyclable, and uses 79% less energy than virgin plastic.

PureCycle’s Business Plan Moving Forward

The company’s first plant is in Ironton Ohio. The company has two more lines under construction in Augusta, Georgia where they will produce >300 million pounds of recycled resin. They broke ground in March 2022.

The Augusta facility will eventually produce approximately 1 billion pounds of of PureCycle’s ultra-pure recycled (UPR) polypropylene resin, called PureFive.

The company had a busy first quarter.

On January 17, 2023, PureCycle and the Port of Antwerp Bruges announced the company’s first European polypropylene recycling facility in Belgium. Initially, the project will produce up to 130 million pounds. But it will be expandable to up to 520 million pounds. First construction will commence in early 2024, with production expected in late 2026.

On March 3, 2023, PUreCycle and iSustain Recycling announced an agreement to source and divert up to 10 million pounds of polypropylene waste from landfills and waterways. The two companies will work together to target post-use polypropylene and packaging materials that aren’t typically recycled.

On March 16, 2023, the company announced a partnership with Formerra, a leading engineered materials distributor. Formerra will be the primary North American distributor of PureCycle’s PureFive resin.

Formerra CEO Cathy Dodd, said:

Addressing the world’s most pressing sustainability challenges is a responsibility we all share. We are excited to bring PureCycle resin to our expansive materials lineup, because this material aligns with our strengths – ingenuity, technical expertise, and sustainable growth. Our customers will now have a game-changing solution to help them meet their environmental sustainability goals. In addition, our experienced technical team will be able to work with PureCycle to customize the material to meet specific customer needs.

On March 17, 2023, PureCycle and Mitsui signed a “heads of agreement” to develop and operate a polypropylene recycling plant in Japan. Mitsui sees “sustainability management and the evolution of ESG” as key areas of its corporate strategy.

This will be the company’s second facility in Asia. PureCycle already has a planned polypropylene recycling plant slated to open in 2025 in South Korea.

This was a deluge of news that caught my eye, originally. The company is moving forward quickly. They are on the brink of producing material and generating revenue. The company is on the brink of going from an innovative idea to an actual business.

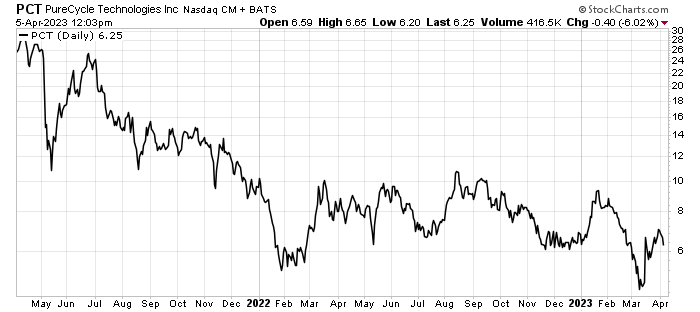

At the same time, the stock itself sold off, as you can see here:

That means we have an opportunity.

But we need to review the risks and potential rewards

The first risk is capital. The company currently has $326 million in cash and securities. They have $249.6 million in debt.

Many of these startups run out of cash just before they cross the finish line. But PureCycle just took care of that. The company secured at $150 million line of credit for working capital. They plan on pursuing more capital raises to fund construction at the Augusta project

As of the year end 2022, the company spent or committed to spend $185.7 million on long-lead equipment for the first part of the Augusta project.

The second risk is that Ironton doesn’t go into production on time. That actually occurred already. The company’s original production deadline was December 1, 2022. They missed that deadline due to some engineering glitches, delivery delays, and equipment damage that delayed commissioning.

That impacted the share price as well.

However, on March 15th, the company issued a press release confirming first production in April 2023.

Action to Take: Buy PureCycle Technologies (Nasdaq: PCT) and use a 25% trailing stop.

In summary, PureCycle is an interesting technology play on a $200+ billion problem. We see their expansion out of North America as an exciting first mover advantage. And the ability to penetrate both Europe and Asia is important.

Sincerely,

Matt Badiali