How to Tell What a Company is Worth

Is this stock cheap?

Is it expensive?

How do we know?

A big share price doesn’t mean a company is expensive. That’s why we need to know its market value. Once we know that, we can figure out the value of the company.

What makes a company cheap or expensive comes down to how you measure it. There are lots of ways to figure that out, but the old school way is where to start.

This style works best on companies that have revenue and earn a profit. Traditional businesses.

The simplest valuation measurement is the price to earnings (PE) ratio.

We measure that by dividing the current market value (price) by a year’s worth of earnings. The result is how many years’ worth of earnings it would take to buy the company at the current price.

Market Value/One Year of Earnings = PE Ratio

Here’s a simple example. Let’s say you want to buy a local business, like the car wash. You could use the PE Ratio as a guideline for how much to pay.

Let’s say the car wash earns $10,000 per year in profit and it’s for sale for $1,000,000. Here’s the PE Ratio:

$1,000,000/$10,000 = 100

That gives it a PE of 100 (it would take 100 years at $10,000 per year to cover the $1 million price tag).

That’s one expensive car wash.

You don’t want to pay so much that it would take 100 years to cover your cost…because then you’d never make a profit.

A more reasonable price would be a PE between 5 and 10.

Ideally, the lower the PE, the better the deal you get. It’s not the same in investing, but it’s a good place to start.

There are some problems with PE ratios though. Mainly, because it requires a company to have earnings. And there are many excellent companies that have limited earnings. Particularly with companies in technology.

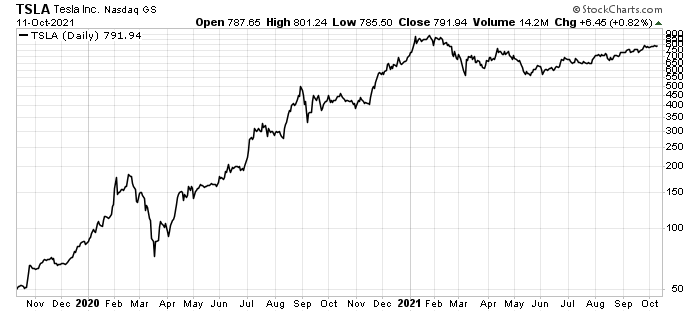

There is a class of “New School” companies that grow quickly, without any earnings. Like Tesla (Nasdaq: TSLA) for example.

These companies trade for crazy PE ratios. TSLA trades for 368 times earnings right now…or 368 years’ worth of current earnings.

You wouldn’t buy Tesla based on a PE Ratio, but it was a fantastic investment. Investors aren’t buying it for this year’s earnings. They buy it because they think its earnings will grow rapidly.

That limits the number of companies we can evaluate with PE Ratios.

Another Old School method for valuation is Price to Book Value (P/BV). Like PE ratios, this starts with Market Value. But then we divide it by Book Value, which is an accounting term for the value of all the company’s physical stuff.

Market Value/Book Value = P/BV

This is a good tool to use for evaluating companies that have lots of plants, equipment, real estate, etc.

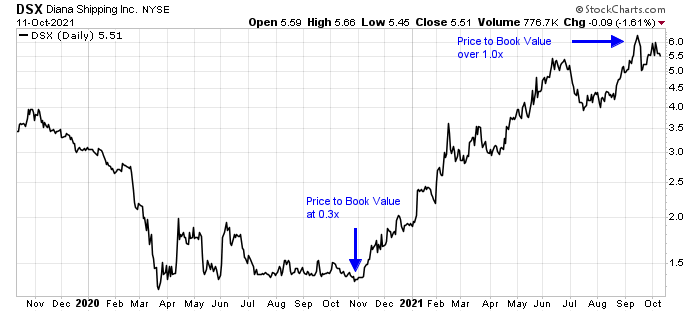

Take Diana Shipping (NYSE: DSX), for example.

This company owns a fleet of cargo ships. Big cargo ships. The stock rarely goes above a P/BV of 1.0. That’s basically the cost to replace the ships.

But it will often trade at a deep discount to the value of its ships. It did that back in September 2020. As the pandemic raged, shipping ground to a halt. The company’s P/BV fell to 0.3.

However, as trade recovered, shares tripled in value. And its P/BV recovered to 1.0.

What we see in this chart is that Diana Shipping’s shares jumped from $1.34 in October 2020 to $6.25 in September 2021. That’s a 366% gain in just under a year.

Both PE and P/BV can be useful in certain situations. They work well when we understand the context. However, they aren’t perfect. And the limitations mean we need to be careful when we apply them.