Uranium Stages Its Comeback

Global policy is pushing major economies toward nuclear power – this commodity will be at the center of it

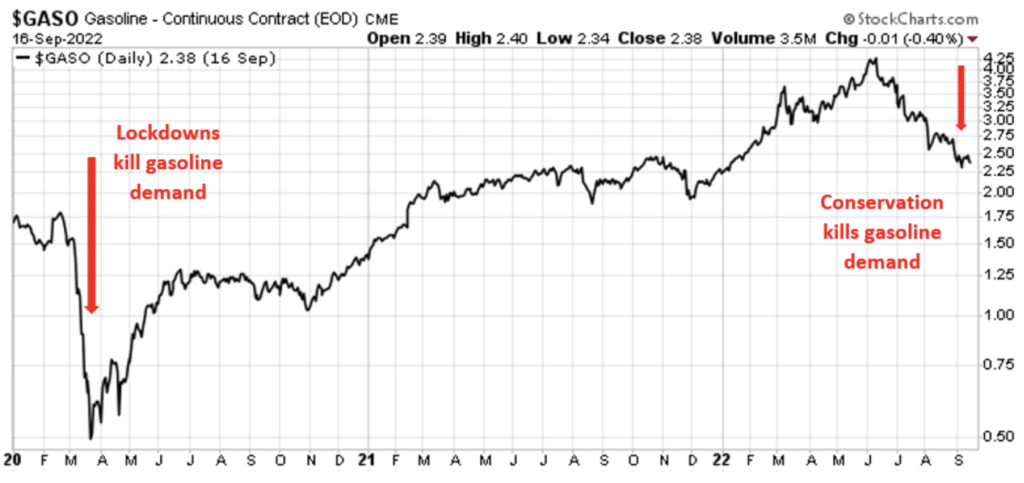

In early 2020, we didn’t drive.

It was early in the pandemic, and without all the drivers on the road, gasoline prices collapsed. With no way of knowing how long the downturn would last, refiners cut production. In some cases, they shut down whole facilities.

When the lockdown lifted, we got back to life quickly… but some of the refineries stayed closed. And others couldn’t reopen fast enough.

They couldn’t keep up with the demand. The price of gasoline soared:

Once we saw that, many of us began to conserve. We drove less. We carpooled. We chose closer vacation spots. Demand for gasoline fell and brought the price down.

Gasoline is the example most of us know best, but that’s a typical supply-demand cycle in natural resources. However, some cycles take much longer and go much higher before they work out.

It’s the same basic principle though: When a commodity is cheap, we use more of it. That goes on until demand exceeds supply, and then the price soars. Then we use less or substitute some other less expensive commodity.

We’re seeing one play out before our eyes.

An 11-Year Bear Market Is Ending

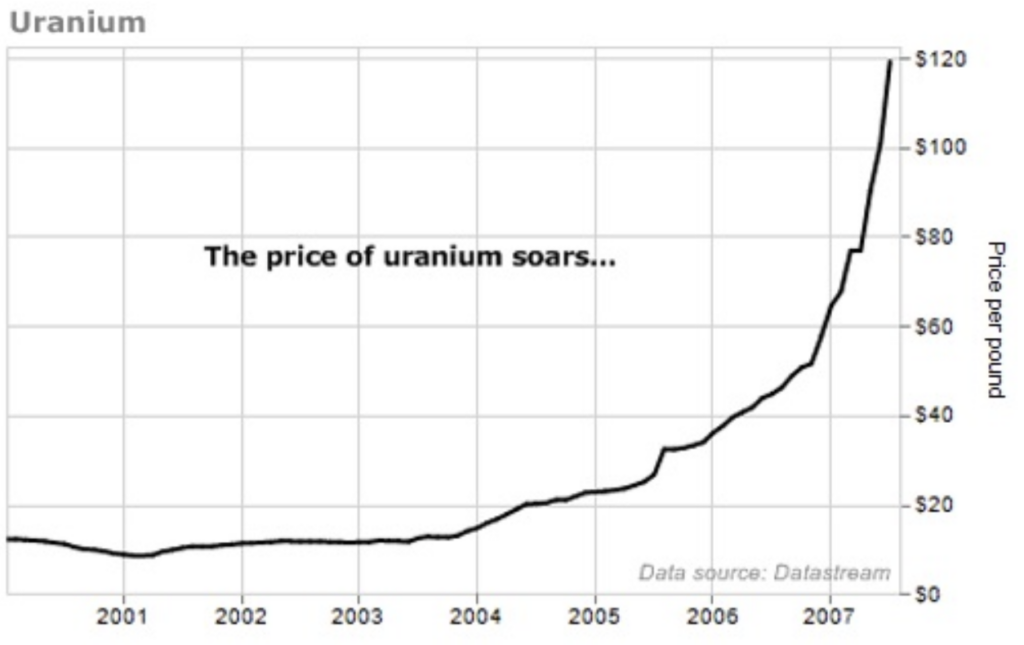

Uranium is a critical fuel for nuclear power plants. And it went through a deep depression in the late 1990s. Oversupply sent the price of uranium plunging.

In 2003, it cost a miner $20 to mine a pound of uranium. But consumers wouldn’t pay more than $15 per pound. It cost $5 more per pound to mine it than the miners could sell it for.

Mines closed. Miners went bankrupt. And no one went looking for new uranium deposits.

It was a classic “bust.”

However, uranium was still getting used. There were still hundreds of nuclear power plants around the world that needed that uranium. For a while, they were able to take advantage of the cheap prices and stockpile the glut. But after years of neglect, the oversupply of uranium got used up… and then the price began to respond:

The uranium mining sector exploded. From 2003 to 2007, uranium exploration investment grew 5,484%. The “bust” was now a “boom,” and investors in uranium mining made a lot of money. But it didn’t last.

In 2011, an earthquake struck the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan. A devastating tsunami followed quickly after. The combined force of those natural disasters disabled the cooling system at the plant. Three reactors melted down, and the whole plant went offline.

At the time, Japan was leading the world in civil nuclear power. But, in response to the accident, it shut down plants all over the country. Before the disaster, nuclear power supplied 25% of Japan’s electricity. By 2014, it made up less than 1%.

And the world followed Japan’s lead. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, from 2011 to 2020, 65 reactors were either shut down or allowed to age out. And about 48 gigawatts of nuclear power capacity went offline around the world.

Not only did that take demand away. It added supply. All the remaining fuel from those plants flooded the market – most plants had ten years of supply built up. It takes a long time to work through a decade of uranium stocks when plants are closing around the world.

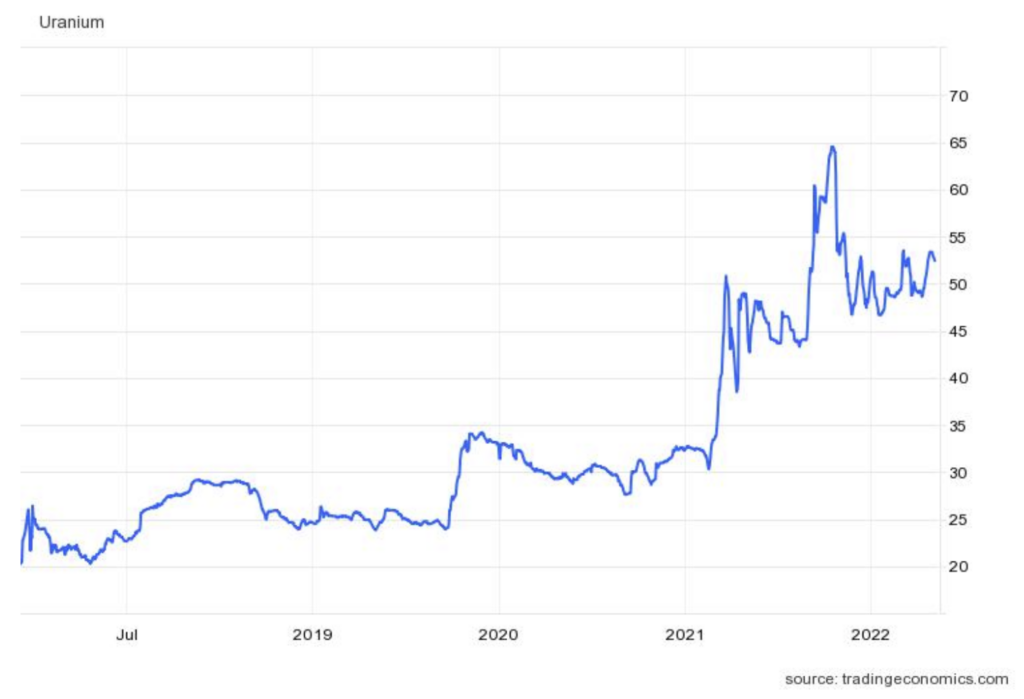

A new uranium bust took hold. By 2016, the price had fallen all the way back to $18.50 per pound.

But the bust looks like it’s finally over.

Just last month, Japan announced it would restart its nuclear power program. The country faced rolling blackouts and a straining power grid. According to Bloomberg, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida asked for nine nuclear reactors to come online by this winter.

And Japan isn’t alone. In September, Germany halted the retirement of two nuclear power plants due to disrupted natural gas deliveries from Russia. France and Slovakia are building several nuclear power plants.

Around the world, there are 56 new nuclear reactors under construction.

This will do two things for the uranium market. First, it will quickly use up any excess supply from formerly closed plants. And second, it will bring in new demand as Japan restarts its mothballed plants.

The uranium price has already more than doubled since its 2016 low:

But we believe that there is room for the price to run higher. Because nuclear power is the best source of baseload, carbon-free electricity available today.

And the nuclear power industry has new plant designs that are like comparing iPhones to old wall-mounted telephones. That includes portable nuclear power plants for off-grid use.

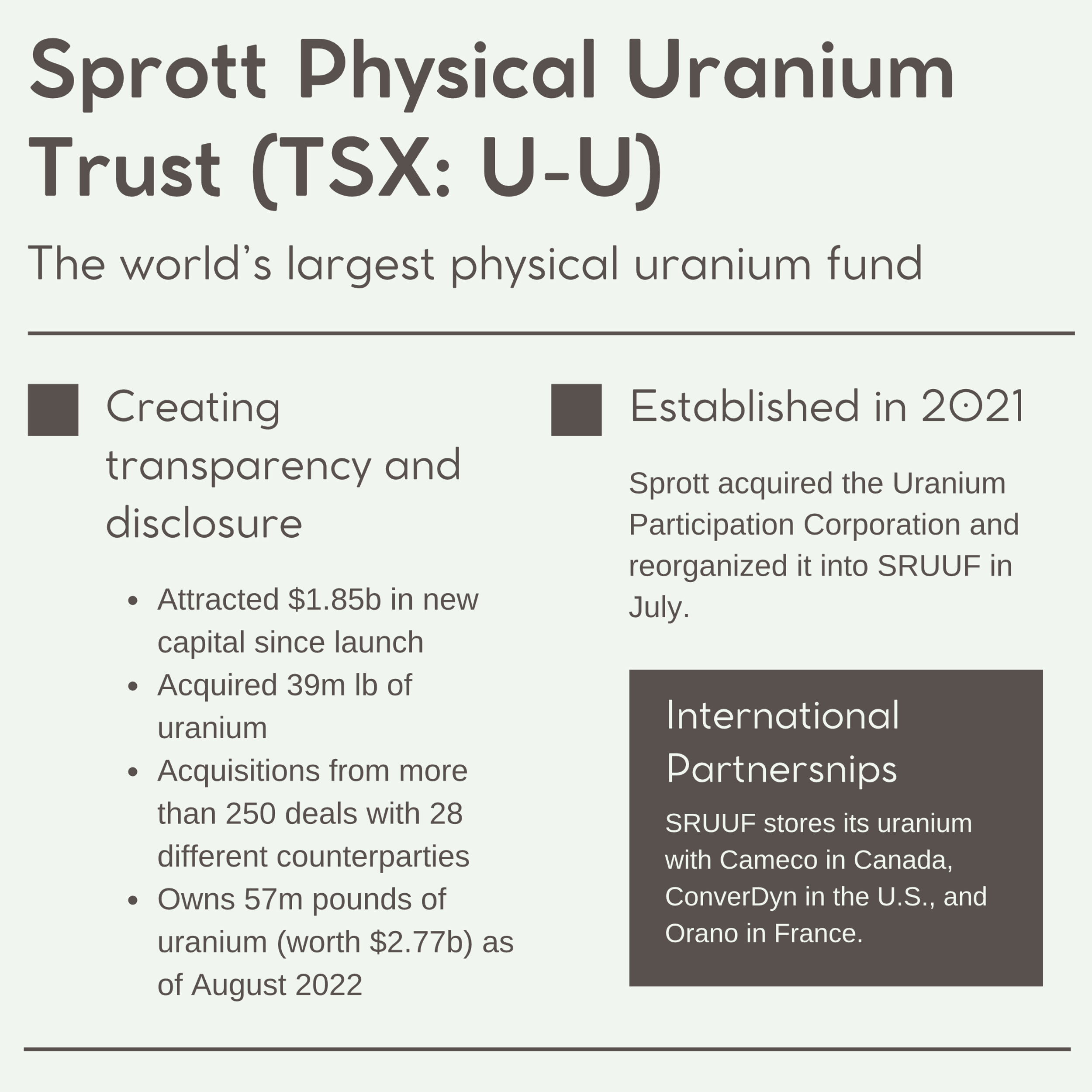

That’s why we want to own a unique company that holds physical uranium: Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (TSX: U-U or OTC: SRUUF). We will be tracking the Toronto stock in our model portfolio, but readers can buy it over the counter in the U.S.

The New Power Paradigm Is Nuclear

Fossil fuels are dirty. We know that.

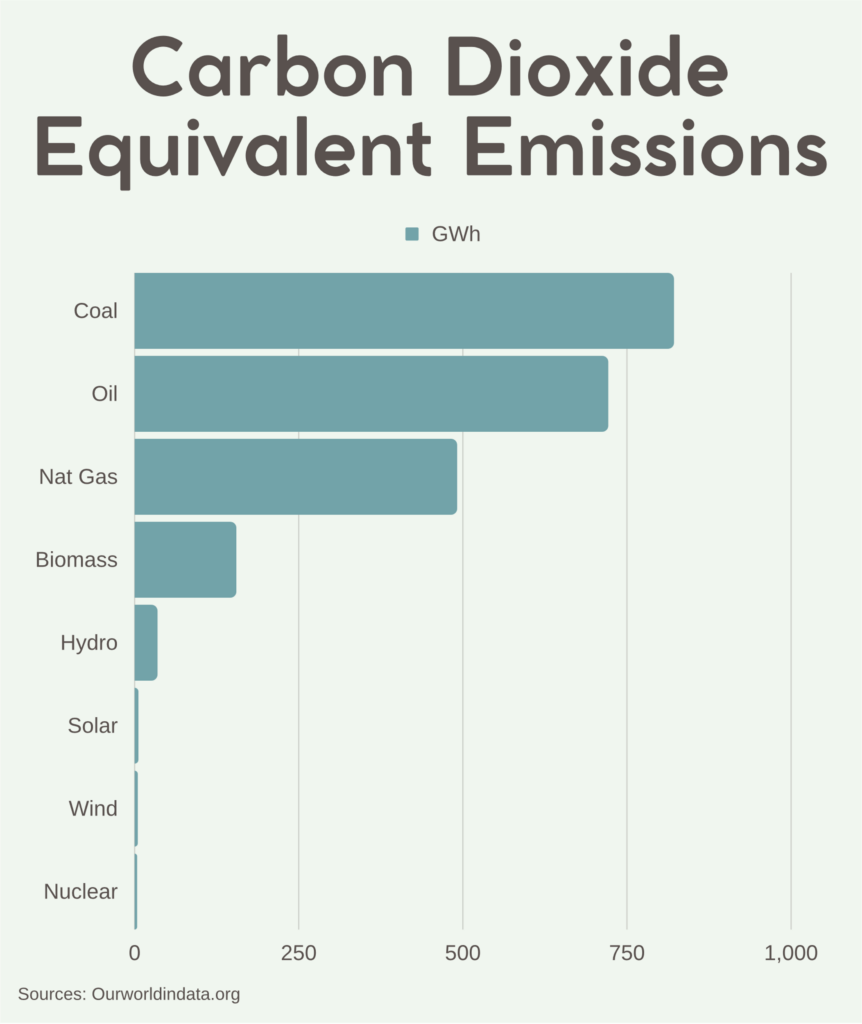

One amazing thing about our political rhetoric over the past few years is we don’t hear enough about nuclear power. It’s available. It’s reliable. And – though this may surprise you – it’s clean:

Few realize that nuclear produces less carbon than wind, solar, or hydropower per unit of energy produced.

But they soon will.

U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm recently appointed Kathryn Huff to her team. Huff was a professor and led the Advanced Reactors and Fuel Cycles Research Group at the University of Illinois. She has focused on nuclear her whole career. Huff will help develop a full uranium strategy in the US.

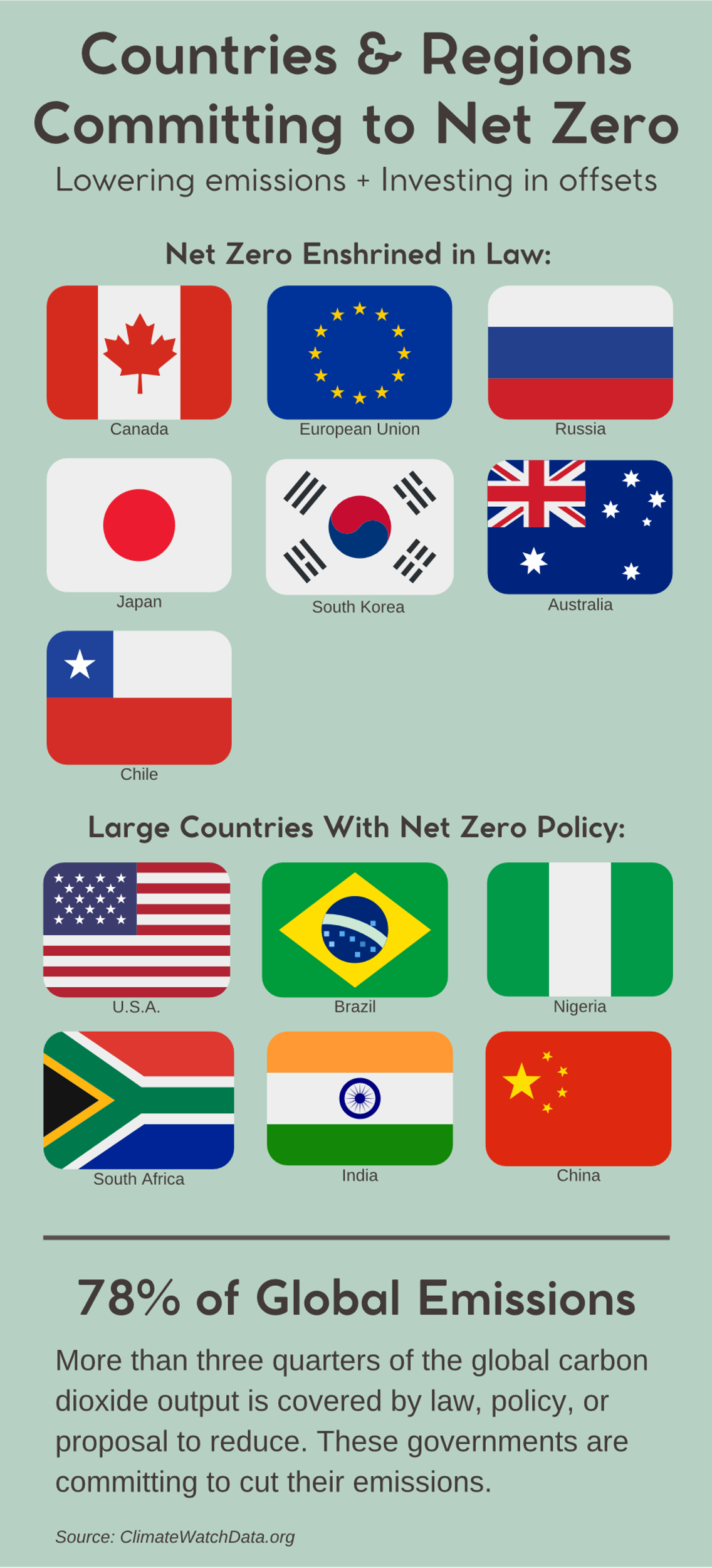

But this effort isn’t just in the states. 83 countries now have a net-zero carbon emission target:

Governments around the world are getting serious about this issue.

Uranium is a global market, but global players are backing away from each other.

Russia became a pariah by invading Ukraine.

Much of the rest of the world has abandoned or liquidated hundreds of billions of dollars of investments there. Russia is a major exporter of uranium.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, it could cost as much as $1 billion. And less supply means the price will rise, assuming steady or more demand.

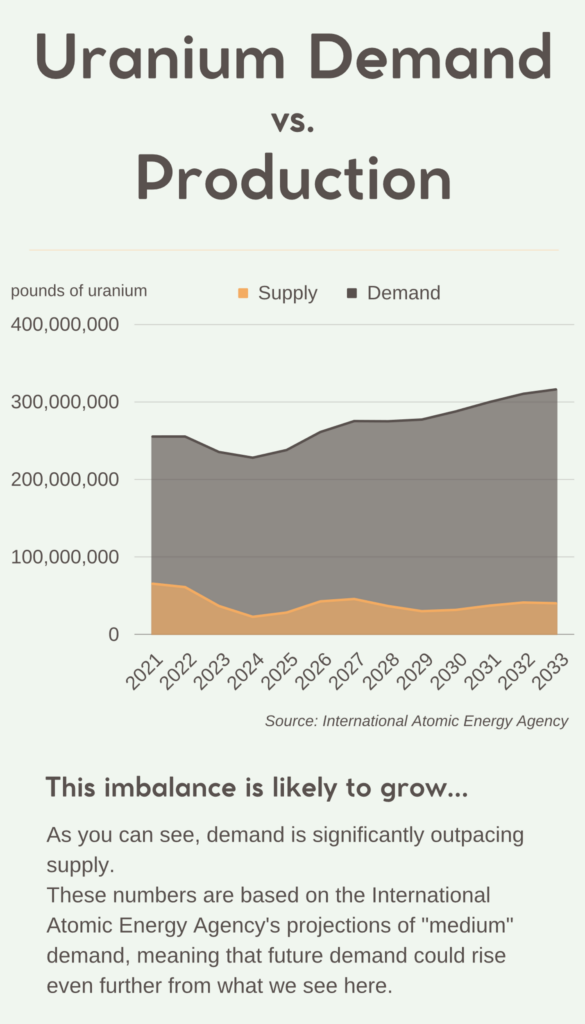

Economics is likely to do that as well. We don’t make enough uranium yet:

The World Nuclear Association says there are 440 nuclear plants connected to the grid today.

While countries will mothball some of these due to age, the number of decommissioning plants is shrinking. Countries like the U.S. and France are extending the lives of their plants… and building more.

But no one is building more than China.

It’s building 18 plants. It’s planning or has proposed 202 more. Russia is building three and has another 48 in the works. (There is a total of 431 planned or proposed plants around the world. That’s nearly as many as are operable today.)

This growth in capacity will fuel the demand for uranium. Buying U-U.TO allows us to benefit from these dynamics.

Sprott Physical Uranium Trust

The trust’s manager says its holdings will continue to grow.

As it controls greater portions of global uranium, its import on the world stage will rise as well.

As the world sources energy supply from places other than Russia, it will realize a decrease in supply and an increase in prices. And the current price of uranium is too low.

Recommendation: Buy shares of Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (TSX: U-U). We believe it will grow between 20% and 100% through its purchase and the appreciation of uranium. (We will be tracking the Toronto stock, but it also trades over the counter in the U.S. under the symbol SRUUF.)

We see nuclear energy as a major part of the power supply mix for decades into the future. Owning the fuel supply while demand grows is an excellent strategy. The fund charges a 0.35% per year management fee.

This is the second play on uranium in our portfolio. NexGen Energy (NYSE: NXE) is a play on developing a uranium mine. But they aren’t currently producing, so they don’t directly benefit from rising prices. That’s why we’re adding U-U.TO. It will be a direct play on rising uranium prices.

We love the uranium space right now. The boom is just starting. This is definitely a sector where we can do well financially by doing good socially.

Good Investing,

Matt Badiali